A poetic list of things

Kunstnere: Linda Aasaru (Estland), Andrew Bearnot (USA), Erin Dickson (UK), Ditte Hammerstrøm (Danmark), Heidi Bach Hentze (Danmark), Sandra Kosorotova (Estland), Eeva Käsper (Estland), Julia Maria Künnap (Estland), Helen Lee (USA), Jiyong Lee (USA), Eve Margus-Villems (Estland), Reinoud Oudshoorn (Nederland), Julija Pociute (Litauen), Helena Tuudelepp (Estland), Sandra Vaka (Norge), Hanna-Maria Vanaküla (Estland), Sissi Westerberg (Sverige), Karlyn Sutherland (UK), Grethe Sørensen (Danmark) og Wang & Söderström (Sverige/Danmark)

Tittel: Translucency. Tallin Applied Art Triennal

Sted: Kai Art Center, Tallin

Tid: 29. mai – 15. august 2021

The fact that high quality applied art is taking/took over Tallinn this summer has been echoing in my social media feeds for several months now. Initially, I was planning to also write about all the satellite exhibitions, however, in order to slim down this review I am cutting these 24 shows from the menu and focus only on the main exhibition titled Translucency.

The eighth edition of the Tallinn Applied Art Triennial, opened in the capital of Estonia at Kai Art Center until mid-August. Probably the most notable change this time around – and the most surprising for the local artists – was the decision to not announce an open call for the main exhibition. Instead, Stine Bidstrup from Denmark was invited to curate the exhibition and appropriately for a glass artist, she chose translucency as the theme for the show. Why was that surprising? Perhaps because people were afraid that involving a curator from outside the country would mean local artists would be underrepresented and the theme of translucency was also seen as very much connected to the field of glass art, which would place other fields in a disadvantage. Seeing the exhibition, however, evaporated these doubts.

Curating an aesthetic whole can be huge pleasure but also huge pain. But how to make everyone happy? Luckily, the material quality of transparency was not set as the primary condition. Translucency can be expressed in multiple ways. Political decisions can be transparent, but we can also see through lies. Translucency can be understood as light travelling through material it encounters. The sun shines and the light passes through a thin curtain into the room. And at night, the snoring of my neighbour also passes into my room through the walls. In the morning, my bed gleams with the body heat of the person who has just left my side. Thoughts of conversations from the previous day also pass through my head.

Inevitably, I enter a labyrinth with glass walls, when I speak of the exhibition. I see things, yet cannot reach them with my words. How to speak about the cognitive-sensory in a way that creates the same kind of space of perception within the reader? After all, I do not have as many words for light and shadows as, for example, the Sámi people have for snow. How to describe the tenderness evoked by dancing specks of light on the ground, passing through the foliage of a tree swaying in the wind? How to explain the nuances of the joy that swells up within you when you play with a dog completely and sincerely lost in the moment – so that even people, who have never had a dog could get a glimpse of the selfless exaltation?

It would be easy to describe all of this, using physics and physiology. Dopamine, serotonin, adrenaline... It is as easy as describing a wall. A good and strong red brick wall, masterfully made, around half a meter thick, tightly fitted together with mortar. And yet, it says nothing about the dreams of the person who has been falsely imprisoned for years behind that wall. What could the person reading my musings on porcelain, glass or textile take away from this?

Let us try. The scientific method requires systematising the best information in the best possible way. And so, I will try to divide the objects I experienced into seven categories:

1. Things that were conceived in dialogue with material:

Artists who have given their everything to one particular material often create sculptural forms based on what the material allows. It is a dialogue. Like a dancing couple, both parties supporting one another. The artist creates a work in collaboration with the memory and the physical properties hidden within the material. The fragile frozen grids made of thin white porcelain, resembling mathematical structures created by the Danish ceramicist Heidi Bach Hentze are still just tenuous and sheer enough to hold themselves together and survive shipping. As little as possible, as much as necessary. By contrast, the unfired paper clay room created by the Estonian ceramicist Helena Tuudelepp is barely holding on. Fragile like nature. And this is not fragility as weakness but fragility as openness to constant change. The physical world will never be complete and only exists on the cusp of transformation. It only takes one forceful sneeze and Tuudelepp's crumbling walls are once again nothing more than clay dust.

2. Things that entice but never let you in:

The American artist Andrew Bearnot has created a two-layer screen out of a fibre glass window screen. Even though the mute material is fixed to a specific spot in the exhibition space, the movements of the viewer and the distance between the two screens create the optical moiré effect that first hits like an unexpected LSD trip. As the viewer stops moving, so do the waves of pattern on the «screen». The installation only reveals itself fully, as the viewer keeps approaching and retreating. When you are close enough, you have already missed it. When you retreat, you realize you never really arrived.

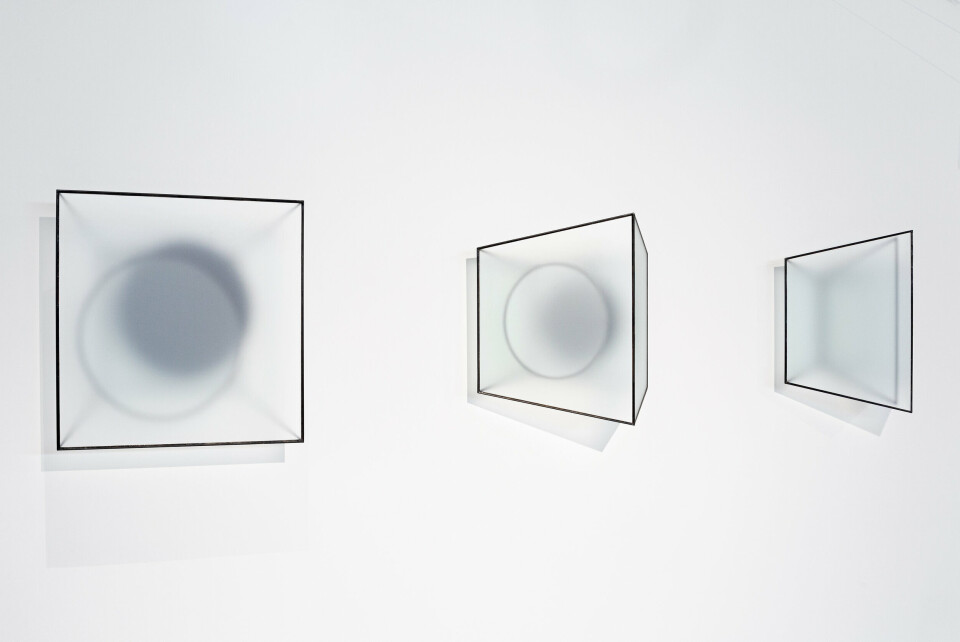

A similar kind of relationship – as if between lovers who never meet – is encoded into the work by the Dutch artist Reinoud Oudshoorn, the arkhitekton-like compositions of steel and frosted glass. To better see the structures hidden behind the glass, I step very close to the sculpture but as I do so, the steel fades out completely. I am too close. I step back. The blurry outline of the steel structure reappears. The structure, meant to be viewed from afar invites you to look closer but fades out of sight as it feels you approaching. Once again, I move away from it. It reappears. I come closer. It disappears. I step away...

3. Things that are very small but contain the whole world:

In this category, we mainly find jewellery. Jewellery as intimate objects, carriers of memory, symbols, means of communication. Jewellery pieces as models of the world. A model always refers to something larger, larger than the object itself ever could be. The Estonian jewellery artist Eve Margus-Villems has carved a basalt ring with a recess dotted with a drop of oil that reflects the viewer back to themselves. Humans have reached all kinds of heights and explored all kinds of depths. Even hell. And it was hell that introduced humans to a new kind of depth. The depth of their soul. You might think you have reached the bottom, but your leg can still sink deeper into the mud. Inevitably, every body of water in the world reflects your own face.

4. Things that explore something:

In contemporary art everyone is exploring something. Relationships, politics, the artist’s own navel – everything is explored and gazed at. In order to find out what someone is exploring you just need to read the accompanying texts next to the artworks. For example, Erin Dickson, a designer from the UK explores «ideas of cultural constructions and craft histories.» In order to do so, she secretly 3D-scanned a fine Venetian chandelier in the Murano glass museum in Italy with her smartphone and once back home, printed the object in plastic.

The American artist Helen Lee «...investigates the morphological and changing nature of language across cultures.» The Lithuanian Julija Pociūtė «...focuses on illusion, reflection, memory and the dual and temporary relationship between humans and their environment.» The Norwegian artist Sandra Vaka «...explores questions concerning our relationship with technological innovations, climate change and consumption, as well as bodily and sensory perception.» Evidently, in addition to exploring, according to the texts, artists also love to investigate, focus on, approach, interpret and analyse.

5. Things you know what are but they are not what you think:

Applied art is so charming because it invites an abundance of connotations. As you become immersed in the field, the question whether something is art or design is no longer relevant. Instead, I look at a chair. It is a chair even when I cannot sit on it. A wooden block in a farm yard is a chair. A redwood throne covered with foam-like baroque gold brocade is a chair. An IKEA stool in vacuum packaging that fits into your backpack is a chair.

The pieces that the Danish artist Ditte Hammerstrøm is exhibiting are also chairs. At first glance, it is difficult to say, where one chair begins and the other ends. The chairs overlap like an image on a frozen computer screen. The repetition in the construction intertwines into a delirious optical illusion. And despite their functional absurd, they are still, above all, chairs.

6. Things that are spaces without doors:

The optical illusion is the king of trickery. Magicians, desert mirages, hallucinations. They make a fool out of me but do not take me to the king’s court. Under the guise of translucency, many objects that rely on illusion and deception have found their way into the exhibition. Soap that presents itself as glass. Surface that evokes space. Refractions of light that gleam from the inside of a mass of material.

The Estonian jewellery artist Julia Maria Künnap is known for creating jewellery that uses mimicry as its guiding principle. Rock crystals in her jewellery seem to melt. Precious stones sprout like early spring nephrite seeds. Crumpled up cacholong and lazurite resembling a brush stroke. At the exhibition, she is showing fabric carved of onyx. It is not translucent, yet hints at the underlying structure that gives the piece its form. And what is the underlying structure? An illusion.

7. Things that want to be saved:

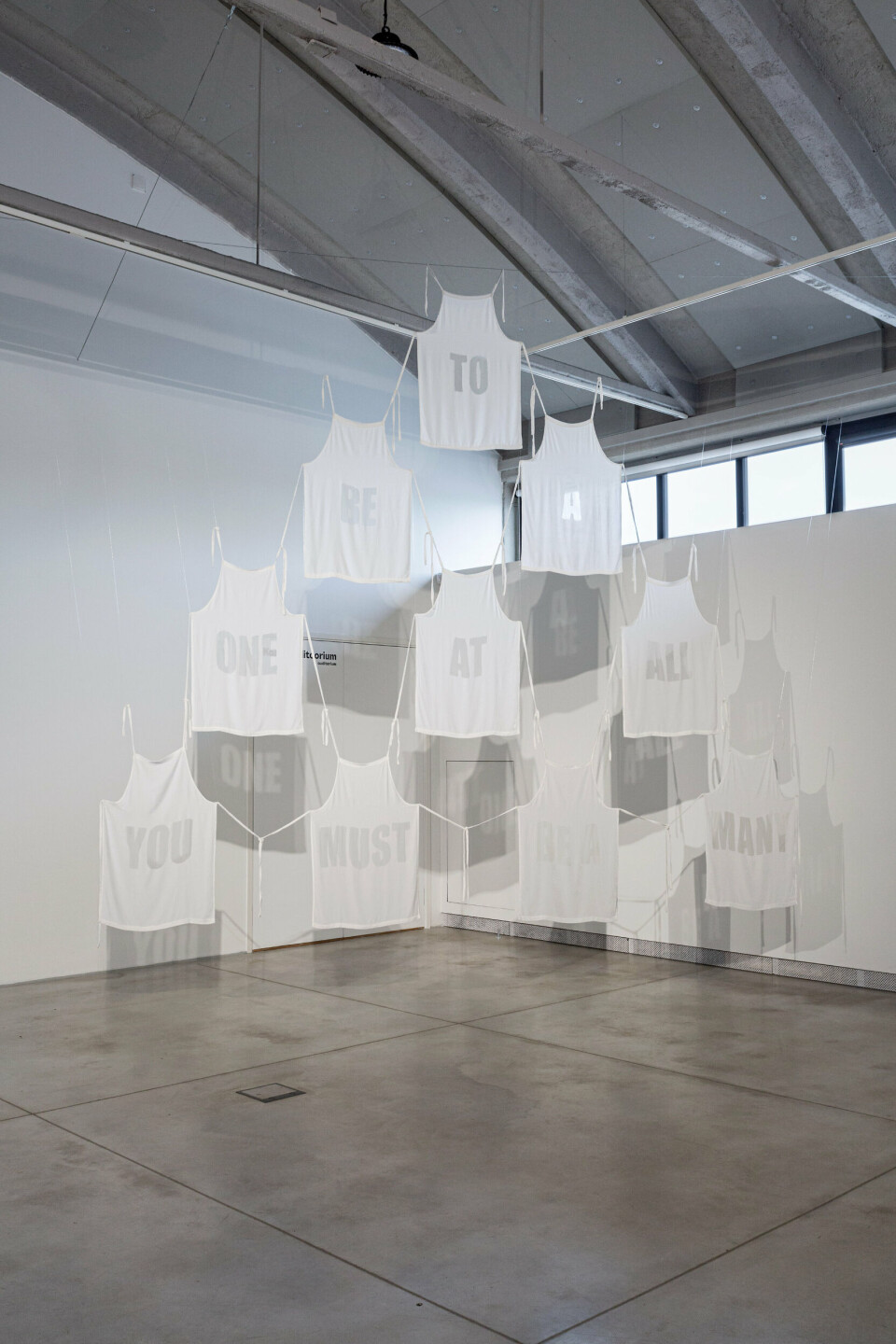

The work with the clearest social message at the exhibition is the installation by the Estonian textile artist Sandra Kosorotova. It consists of shirts with words cut out in the front, hung in a pyramid shape. The words spell out «To be a one at all you must be a many». Amen.

Urmas Lüüs