Ethics of our entanglement with the Earth

Tittel: Earth, Wind, Fire, Water

Kunstnere: Hildur Bjarnadóttir (IS), Ebba Bohlin (SE), Fellesskapsprosjektet å Fortette Byen (Sápmi/NO), Alma Heikkilä (FI), Karoline Hjorth & Riitta Ikonen (NO/FI), Guðjón Ketilsson (IS), Kasper Kjeldgaard (DK), Stian Korntved Ruud (NO), Ivana Králíková (CZ/SE), Valentin Manz (DE/NO), Britta Marakatt-Labba (Sápmi/SE), Pekka Paikkari (FI), Louise Sidelmann (DK), Brynjar Sigurðarson & Veronika Sedlmair (IS/DE), Ida Wieth (DK), Hedvig Winge (NO) og Charlotta Östlund (SE/FI)

Kurator: Randi Grov Berger

Sted: F 15, Jeløya, Moss

Tid: 16. juni – 4. oktober 2020

Although meaning it will miss its fiftieth anniversary next year, the Tendenser exhibition switching to a biennale periodicity from 2014 has potentially enabled curators of the exhibition chance to better develop exhibition ideas and relationships with prospective participants. For the forty-fourth edition, curator Randi Grov Berger took the reins, looking for the exhibition Earth, Wind, Fire, Water to offer «different ways to think about, with, and through contemporary crafts.»

It is tempting to read periodic exhibitions solely in terms of the contemporaneousness of the work, bring the temporal «frame» of the period since the previous exhibition and any particular experiences or events to bear on an exhibition, rather than relying on a loosely applied exhibition «theme» that looks to affect a sense of social urgency or «relevance» but disappears under scrutiny. Given the historically major set of events happening in the world in the last few months – Covid-19 and the anti-racism protests – it seems unfair, not to say difficult, to try to read this edition of Tendenser in terms of what has happened recently.

As its title suggests, the exhibition takes its cue from fundamental material elements. This focus is conceptually underwritten by the now much-used theorisations of new materialism, a philosophical mode of thought emerging most clearly around the turn of the century and hugely in vogue in art in the last decade. A thinker often included within new materialism and very much aligned with the concerns outlined in Earth, Wind, Fire, Water is Karen Barad, a philosopher-physicist with a theoretical physics background in quantum field theory. The huge scope and major perspective shifts of Barad’s work makes it extremely difficult to give a succinct outline of it for my purposes here, but one fundamental tenet of quantum physics in her work might be useful to bring up: the empirically verified claim that observation of a thing changes the thing itself, and, therefore, an apparatus and phenomenon – knowledge of a thing and the thing – are «entangled» and typified by «intra-action» (in mutual and transformational contact, as opposed to the limitations and clear boundaries of interaction). Barad extends this into ethics (in fact, as per her philosophy, she understands ethics as always imbricated in knowing and things): Our entanglement with the world means that ethics, and particularly responsibility, are not «chosen» by individuals but are actually part of the material fabric of life, «an incarnate relation that precedes the intentionality of consciousness.»[1] Here, then, we have a slightly developed, if quite abstact, idea of how to possibly consider dialogue with materials as also implicitly bound to an environmental ethics.

A meticulous reading of Earth, Wind, Fire, Water aside the work of Barad would no doubt be an illuminating undertaking; however, a few of the works seem to stretch the conceptual underpinning in a way I think might help a reflection on what is at stake in such an exhibition.

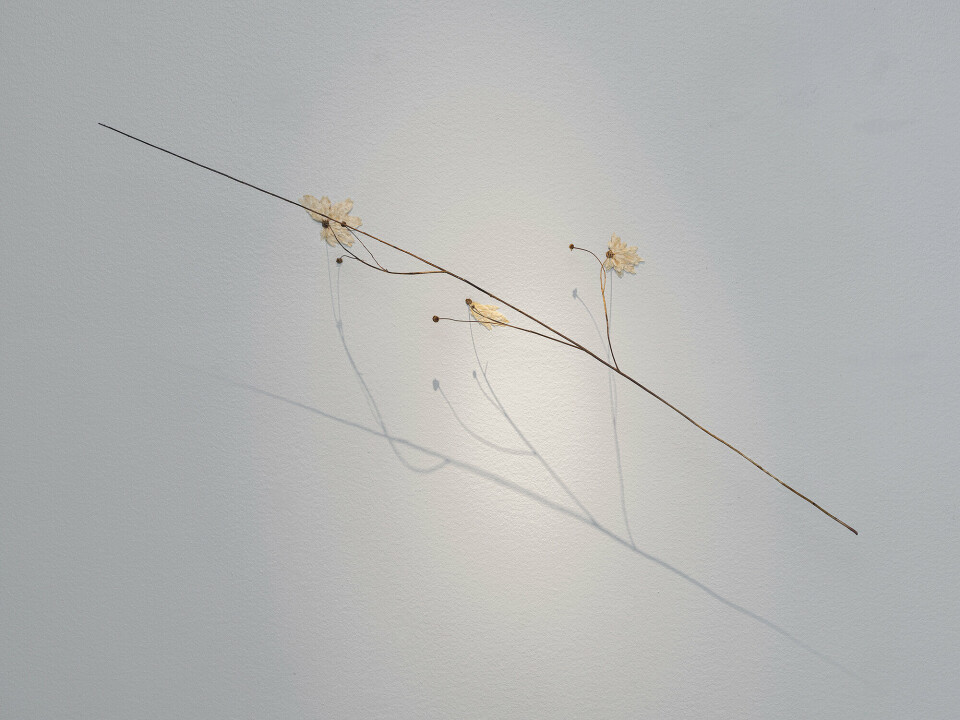

Charlotta Östlund’s small work Arrow proposes a few questions that begin to do this. In one of her two wall-affixed dried plant cuttings, one of four pieces presented at F 15, Östlund performs a reversal: seductive flowers become the supporting surface area and the previously supportive stem, with the help of the title, becomes the foregrounded object or sign (most likely the former, but potentially the latter). Seduction, then, becomes either the structural fixture for either the representation of an object (arrow as weapon) or for the blunt semiotics of pointing (arrow as sign).

In functionalising the seductive façade of flowers as surface area, we might consider Arrow to assert that seduction, and perhaps particularly seduction within an art exhibition, needs to be put to use in a different way in the struggle for (environmental) change; environments are saturated with violence and communication, but these are also the hallmarks of human harnessing of, and sense of domination over, their surroundings.

Distilling the aesthetic crosshatching of the violence and communication of human relations with the world in something so delicate as a dried plant cutting, Arrow’s subtly Baroque gesture is a challenge to Earth, Wind, Fire, Water. It professes to the difficulty of initiating a dialogue about the need for a revolution of environmental concern and policy in an art exhibition without reifying the idea of «nature» as beautiful, or understanding the desire for a «return to nature» as anything but a privileged wish of those untouched by the environmental and socio-cultural destruction of, for example, the northern reaches of the Nordic region in which lives of people, including people identifying as Sámi, are being ignored.

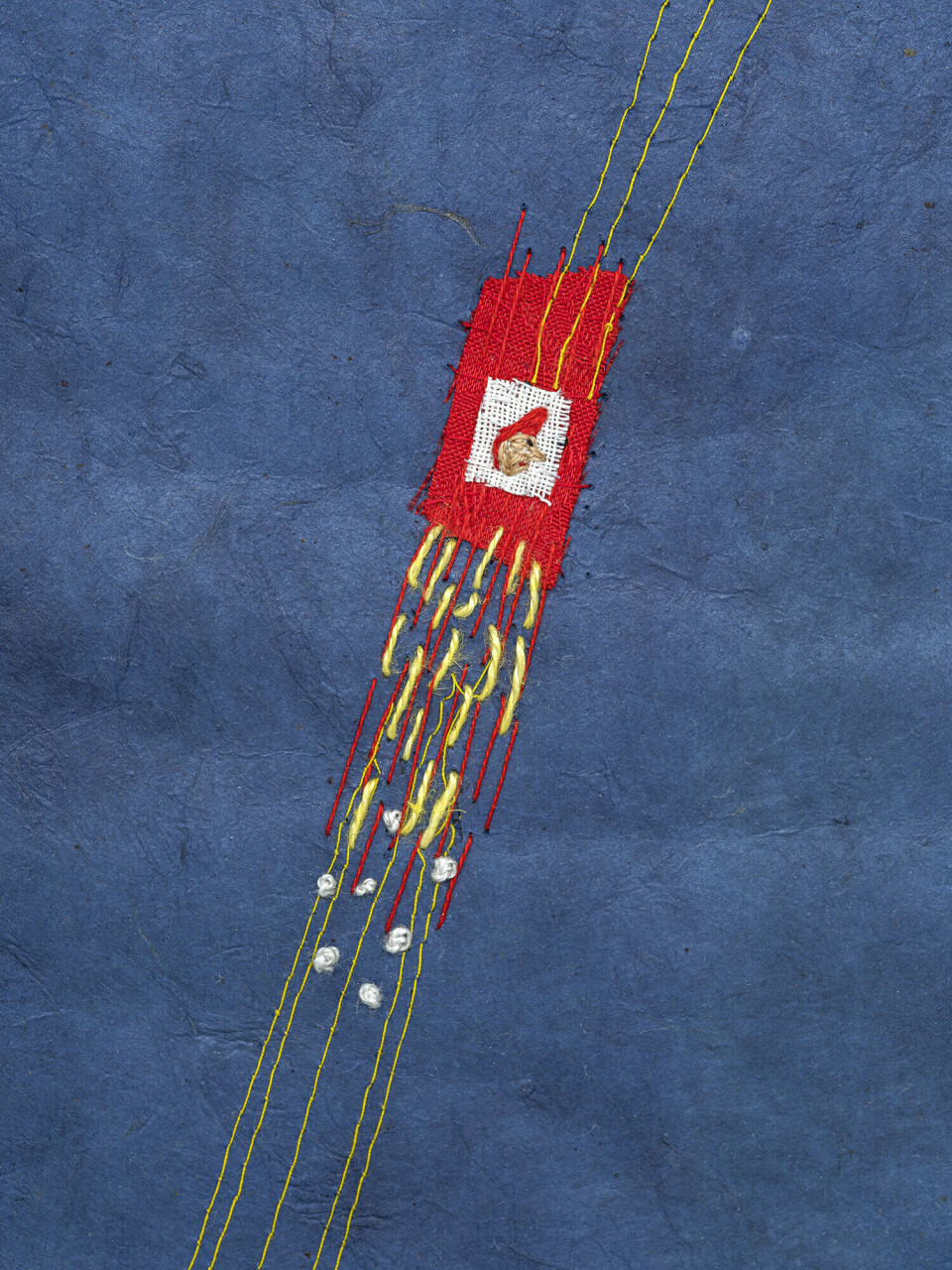

There are two artists exhibiting in Earth, Wind, Fire, Water that identify as Sámi: One, Britta Marakatt-Labba, has two works Skuggor and Kosmos sharing a room with two of Östlund’s pieces. Kosmos emphasises the cosmic and mythological side of Marakatt-Labba’s work, whilst Skuggor (translation: Shadows), with sled-riding figures wearing hats resembling Ládjogahpir (a horned hat), veers more towards a snapshot of a story of travel. Randi Grov Berger kindly gave me access to the forthcoming book around the exhibition. In it, a text by Jessica Hemmings expands on the specific symbolism in Skuggor:

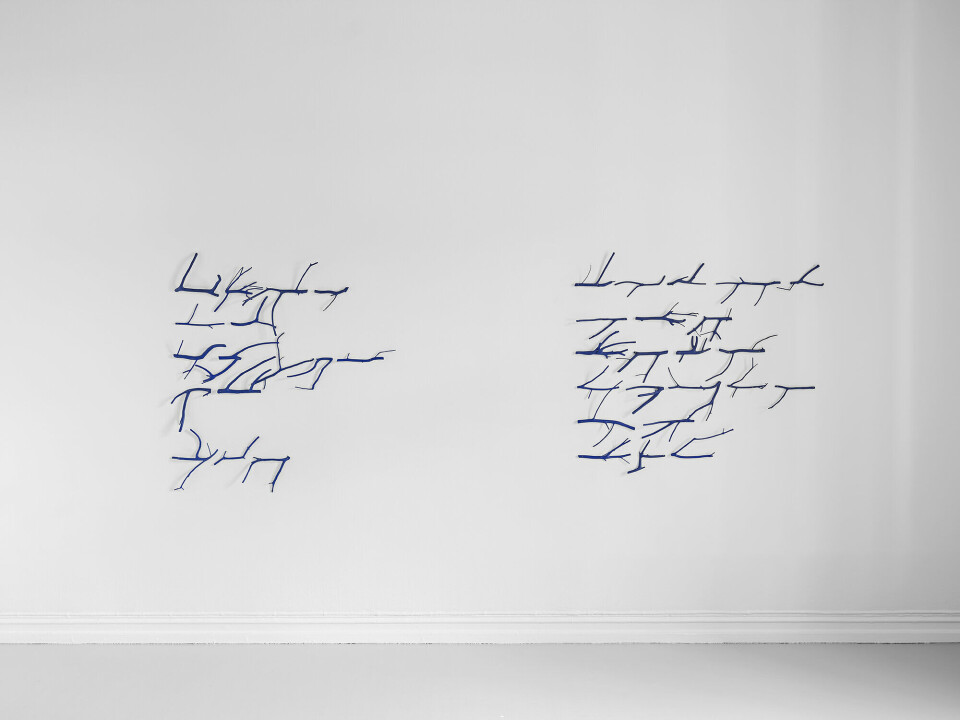

The other exhibiting artist identifying as Sámi, Joar Nango, presents work made as part of Felleskapsprojektet å Fortette Byen (FFB), a group he founded with architects Håvard Arnhoff and Eystein Talleraas in 2010. Their work, Meahccetrošša/Matatu: Eai čuovo mearriduvvon luottaid, eai ge vissis njuolggadusaid [They don’t follow routes and they don’t conform to regulated order —Norwegian translation by curator: De følger ikke vedtatte veier, ei heller bestemte regler] perhaps speaks to Grov Berger’s work as founding director of the gallery Entrée in Bergen at which she presents a wide range of art practices. FFB’s contribution is an intriguing addition to the exhibition in that it is obliquely related to the curatorial concept.

Made of reclaimed wood and simply attached to the gallery’s sea-facing manor house façade, the work’s title is written in Northern Sámi in a compact and angular typography. The temporary feeling of the work – almost like it is a sketch for a «public art» commission – is clearly aligned with the improvisatory practices and quasi-fugitivity Joar Nango considers important to the ways of living of people identifying as Sámi (linking somewhat to Marakatt-Labba’s Skuggor too).[3] The work is like a motto of the (de)formation of such ways of living under quasi-colonial pressure from the Nordic countries (and Russia). The «they» (in the English translation, at least) creates a distance upon articulation of the phrase: it could be both a description and an accusation, spoken by a commentator/storyteller or a plaintiff.

earth:NOW:being, the three-projection video piece made by Christine Cynn is documentation of the fifteen-week-long participatory project In the Pits by Valentin Manz with a vaguely ritualistic, dynamic percussion soundtrack provided by Giles Kwakeulati King-Ashong (otherwise known as Kwake bass). The videos show Church Farm, Ardeley (UK) where Manz and others sculpted seven large clay vessels in the British countryside, conducting workshops for children in the process.

Like FFB’s work, earth:NOW:being digs away at the edges of Earth, Wind, Fire, Water in that, with the addition of the soundtrack, the documentary footage becomes something else rather than just the documentation or result of a crafting process. The editing and use of three screens in the film is particularly of note as occasionally the same (or very similar) footage is shown on more than one screen simultaneously, sometimes slightly staggered sometimes in synchrony, slowing the pace of the film yet quickening the eye as you try to verify if it is in fact the same footage you are seeing. All being well with the global pandemic, Manz himself will be at F 15 in September to conduct a participatory event in the gallery’s workshop.

The theoretical innovations of new materialist thinkers often seem easily, if not uncannily, cooptable as a smattering of newness and philosophical/theoretical «relevance» appendable to any situation, perfect for art’s nervous hospitality as well as making it perfect museum material. The work that must be done by citers, thinkers, and those working with art, is the labour of politicising this thinking – teasing out where theoretical speculation veers towards material for financial speculation.

Earth, Wind, Fire, Water invites the question not only of how an exhibition might contribute to any given theoretical ballast from philosophy, but perhaps more specifically, as my reflections on Charlotta Östlund’s Arrow start to tease out, how the specific trappings of exhibition-making present particular conditions – both hurdles and opportunities – for thinking about the ethics of our entanglement with the Earth through, as Grov Berger imagines, thinking «about, with, and through contemporary crafts.»

Johnny Herbert

[1] Karen Barad, ‘Quantum Entanglements and Hauntological Relations of Inheritance: Dis/continuities, SpaceTime Enfoldings, and Justice-to-come’.

[2] Jessica Hemmings, ‘Fugitive Nature’, Earth, Wind, Fire, Water (forthcoming).

[3] See ‘Duodji as part of philosophy and cosmology’, a conversation between Nango and Namita Gupta Wiggers on the Norwegian Crafts website: https://www.norwegiancrafts.no/articles/duodji-as-part-of-philosophy-and-cosmology